Things that make us smart: Defining human attributes in the age of the machine

Book

Norman, D. A. (1993). Things that make us smart: Defining human attributes in the age of the machine. New York, NY: Addison-Wesley Publishing Company.

General Outline

There are two kinds of cognition experiential and reflective which categorize the business tasks at hand and have enormous implications regarding task structuring in design.

There are three kinds of learning—accretion, tuning, and restructuring—that must be mapped to the two kinds of cognition and which, in turn, have enormous implications for those of us engaged in developing systems which ensure that task completion is primary, learning is secondary to the task at hand.

Performance is dependent primarily on the cognitive artifacts of the context - and without good ones human beings perform poorly or cannot perform at all.

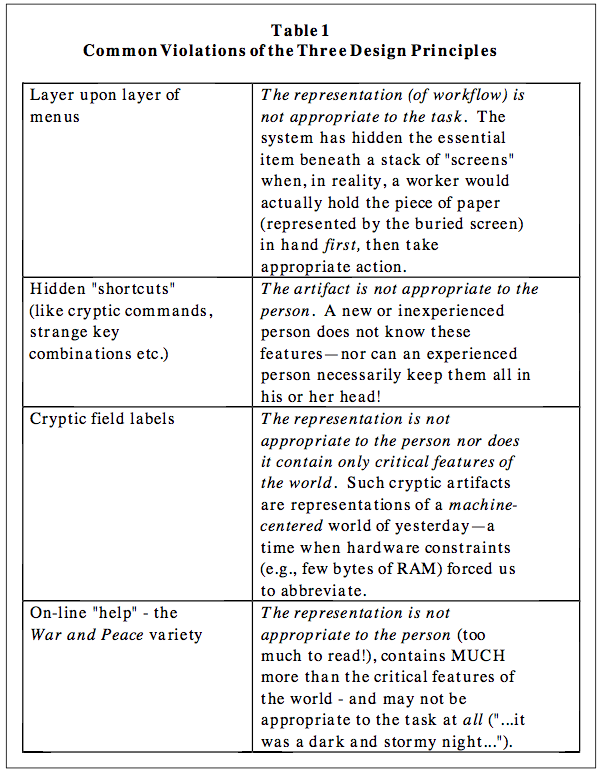

There are essentially three design principles:

The representation must match the task

The artifact must match the person

The passive constraints that are imposed by artifacts must focus (abstract) the critical features of the world

Design should be like telling a story. The design team should start by considering the tasks that the artifact is intended to serve and the people who will use it. (p. 105)

Want to guarantee error? Then devise tasks that require using the memory for details, that require devoting extended periods of attention to unchanging situations. If the environment consists of rows of similar-appearing controls or displays, error in reading or operating them is almost guaranteed to happen. (p. 138)

The power of information artifacts is that they provide an unrivaled opportunity to enhance our lives. The danger is that they can stress our everyday existence. (p. 105)

The trick in designing technology is to provide situations that minimize error, that minimize the impact of error, and that maximize the chance of discovering error once

it has been committed. The human- centered way. (p. 138)

Is there a way to transform the hard technology of computers...into a soft technology suitable for people? Yes, I think so. The correct approach...is to start with the needs of the human users of the system, not with the requirements of the technology. (p. 237)

A place for everything and every- thing in its place—if only you can keep track of the places. (p. 159)

“What can technology do to help?” is almost always the wrong question. (p. 152)

Stories are important cognitive events, for they encapsulate, into one package, information, knowledge, context, and emotion. (p. 129)

[Ahh, if only each system told a story... —GJD]

Grudin’s law: When those who benefit are not those who do the work, then the technology is likely to fail or, at least, be subverted. ( p . 113) [Re: voice messaging systems.]

The new-fashioned information artifacts take on arbitrary shape and form. There is no natural mapping, no natural principles of operation. The critical operations all take place invisibly through internal representations. If we are able to use these artifacts easily and efficiently, the designers have to provide us with assistance, with understandable, coherent structure. We are in the hands of all designers, who have the power to make the artifact meaningful, to provide substance and richness, and to make its use support the activities of interest. The best of the artifacts will become invisible, fitting the task so perfectly that they merge with it. They will be a delight to use. (p. 105)